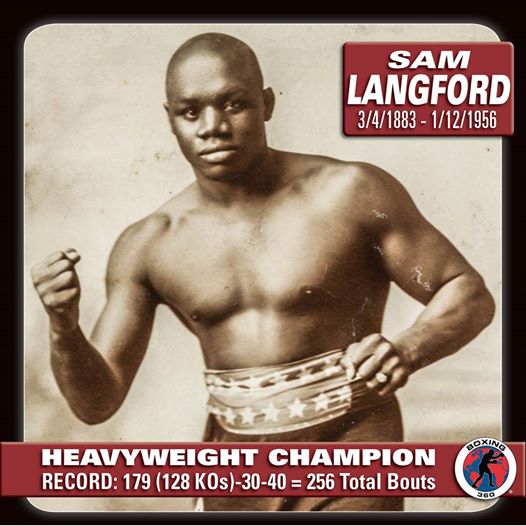

Whenever boxing fans debate the question, the name most often mentioned is that of Sugar Ray Robinson. However, many boxing historians would argue in favor of Sam Langford, a lesser-known fighter born in Weymouth, Nova Scotia, in 1886.

During the first quarter of the twentieth century, the prospect of facing the five-foot-seven-inch dynamo, who weighed no more than 175 pounds at his peak, struck terror in the hearts of most of his contemporaries, including heavyweight champions Jack Johnson and Jack Dempsey.

In June 1916, the 21-year-old Dempsey quickly declined an opportunity to face an aging Langford. Recalling the incident years later in his autobiography, Dempsey wrote, “The Hell I feared no man. There was one man, he was even smaller than I, and I wouldn’t fight because I knew he would flatten me. I was afraid of Sam Langford.”

Jack Johnson, on the other hand, did face Langford, once, in April 1906, when Langford was only a 20-year-old lightweight who gave up over 40 pounds to the 28-year- old heavyweight contender. Johnson won a convincing 15-round decision over the youngster, but discovered just how tough the smaller fighter was and what kind of dynamite he carried in his fists.

Two and a half years later, Johnson won the heavyweight championship by defeating Tommy Burns. Over the ensuing years, Langford and his manager, Joe Woodman, hounded Johnson in futile pursuit of an opportunity to fight for the title.

“Nobody will pay to see two black men fight for the title,” Johnson said However, when Johnson grew weary of Australian boxing promoter Hugh “Huge Deal”’ McIntosh’s efforts to arrange a match with Langford, he admitted that he had no wish to face Langford again. “I don’t want to fight that little smoke,” said Johnson. “He’s got a chance to win against anyone in the world. I’m the first black champion and I’m going to be the last.”

Years later, Johnson confided to New England Sports Museum trustee Kevin Aylwood, “Sam Langford was the toughest little son of a bitch that ever lived.”

Despite participating in over 300 professional bouts in a 24-year ring career (from 1902 to 1926), Langford never won a world title. He defeated reigning lightweight champion Joe Gans by decision in December 1903 but was not recognized as the new champion because he came into the fight two pounds over the lightweight limit. Nine months later Langford fought the world welterweight champion, Joe Walcott, to a 15-round draw in a contest that the majority of those in attendance felt he deserved.

Surprisingly, Langford would never receive another opportunity to fight for a world title. Although he faced middleweight champion Stanley Ketchel in a six-round fight in April 1910, this was a predetermined no-decision contest that was rumored to be a preview for a 45-round title bout on the West Coast later that year. Unfortunately, Ketchel was murdered before that event could be held.

Although Langford began competing as a lightweight and then as a welterweight, once he matured physically, it became more difficult for him to keep within those weight limits. He was also aware of the fact that there was more money in fighting big fellows and subsequently went after heavyweights. Over the years he met and defeated many men much larger than himself: men like “Battling” Jim Johnson, Sam McVey, Sandy Ferguson, Joe Jeannette, Sam McVey, “Big” Bill Tate, George Godfrey and Harry Wills. Some of these fighters towered over Langford, who often also gave up as much as 40 pounds in weight.

One opponent, “Fireman” Jim Flynn, said of Langford’s punching power: “I fought most of the heavyweights, including [Jack] Dempsey and [Jack] Johnson, but Sam could strength a guy colder than any of them. When Langford hit me it felt like someone slugged me with a baseball bat.”

In 1917, Langford completely lost the sight of one eye during a loss against Fred Fulton. Remarkably, he would continue fighting with one eye for another nine years, the last few with limited sight out of his one “good” eye. In 1923 he captured the Mexican heavyweight title in a contest at which he had to rely on his handlers to help guide him into the ring and to his corner. Langford’s assistants were so concerned about his eyesight that they wanted to call the fight off, but Langford refused: He needed the money.

Sam fought for another two years while his eyesight continued to fail, until in August 1925, in his last professional bout, he was forced to quit in the opening round of a fight when it became obvious that he couldn’t see his opponent at all.

By 1944, Langford was blind, all but forgotten and living in poverty in a dingy tenement in Harlem, N.Y. In January of that year, sportswriter Al Laney of the New York Herald Tribune decided to write a story about Langford, a great boxer who had seemingly vanished from the face of the earth.

The search proved futile for quite a while. Many people Laney questioned were not even aware of who Langford was. At least a dozen others but claimed that Langford was dead. Eventually Laney learned that Langford was in fact alive and residing in a building in his city on 139th St. A woman who resided in the building led Laney to a tiny, dirty bedroom at the end of a dark hallway on the third floor. There, Laney found Langford, just one month shy of his fifty-eighth birthday, sitting on the edge of his bed, listening to an old radio.

Langford had 20 cents in his pocket and was subsisting on a few dollars he received each month from a foundation for the blind. Twice a day, two young boys would come by and take him to a restaurant for breakfast and a second meal late in the afternoon. Langford told Laney that he the rest of his time sitting alone in his dark bedroom with only his radio for company.

When he’d gathered the information he needed for his story, Laney went back to the office and banged out the story on his typewriter for the paper. But he didn’t stop there: He was so moved by Langford’s situation that he initiated a drive with a group of New York businessmen and -women that raised $10,892 for a trust fund for Langford. In April of 1945, the money was invested in an insurance company so that Langford would receive an annuity of $49.18 a month for life.

In 1952, Langford moved back to Boston and quietly lived out the remaining years of his life in a private nursing home. He passed away on January 12, 1956, just two months before his seventieth birthday and only ten weeks after being enshrined in the Boxing Hall of Fame. At the time of his induction, Langford was the only non–world titleholder to be so honored.

Sam Langford never regretted his chosen profession and expressed no bitterness or remorse over the loss of his eyesight. He maintained a keen sense of humor and kind disposition throughout his life and always said that boxing provided him with a wealth of memories. In a statement attributed to him a few months before his death, he said, “Don’t nobody need to feel sorry for old Sam. I had plenty of good times. I been all over the world. I fought maybe 600 fights, and every one was a pleasure!”